Now, Even The Wealthy Are Worried About Inequality

The Article: Inequality may spark unrest, Davos elites worry by David Cay Johnston in Al-Jazeera.

The Text: There’s trouble coming as the chasm between the richest of the rich and everyone else continues to widen. So says a report prepared by the World Economic Forum, the nonprofit foundation that hosts its annual conference of business leaders in Davos, Switzerland, popular with the world’s billionaires.

The forum’s 14th annual assessment of risks, issued just ahead of the Davos gathering, makes clear that social instability, whether measured in mere riots or in bloody revolutions, is the likely outcome of increasing inequality.

The report speaks of a lost generation of young people worldwide who are finishing school only to find a paucity of jobs, which in turn creates pressure to lower wages.

“Widening gaps between the richest and poorest citizens threaten social and political stability as well as economic development,” the report said.

Three of the report sponsors are specialists in pricing risk, the American insurance broker and risk advisory firm Marsh & McLennan and the European insurers Swiss Re and Zurich Insurance Group.

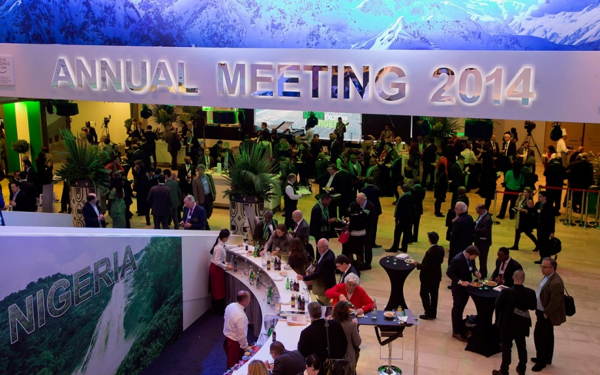

The four-day Davos conference, which begins today, will draw six dozen or so billionaires this year as well as several hundred other people rich enough to have their own jets. Davos will also draw a far larger crowd of government officials, vendors of financial services and journalists.

That those at the apex of the global economy brought forth this report should end the debate over whether inequality poses a problem, but it won’t.

To those who deny inequality is a problem, or herald inequality as an economic good, the report can be dismissed as simply the claims of an interest group. And why trust what billionaires say any more than what a minority of economists, sociologists and writers (including me) has been pointing out for two decades?

Oxfam, the British relief charity, keyed off the Davos report with one of its own that made two powerful points:

The 85 richest humans hold more wealth than the 3.5 billion people who constitute the bottom half.

These disparities in wealth and income result from “political capture,” in which the wealthy use their economic power to make sure “the rules bend to favor the rich, often to the detriment of everyone else. The consequences include the erosion of democratic governance, the pulling apart of social cohesion, and the vanishing of equal opportunities for all.”

Here is a stark indicator of just what happens when the rules are bent to favor the rich, as I have been documenting for many years.

Adjusted for inflation, Americans reported $1.1 trillion more income in 2012 than in 2009, when the Great Recession officially ended midyear. That’s a 15 percent real increase.

Where did that increase go? America’s 16,000 top-earning households enjoyed nearly a third of it. The top 1 percent captured 95 percent of the nation’s income growth. The top 10 percent of Americans, the best-off 31 million people, enjoyed all the national income growth.

As for the vast majority of Americans, the bottom 90 percent, they were worse off in 2012 than during the Great Recession. Even though the economy improved in those years, their wallets shrank until they were 15.7 percent thinner, IRS data analyzed by economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty showed.

Indeed, the vast majority’s average 2012 income fell back to the level of 1966.

You read that right: 1966, when China was called Red, Lyndon Johnson personally turned off lights in the White House to save taxpayers money, the Beatles released “Revolver,” and Barack Obama entered kindergarten in Honolulu.

The puzzle for the Davos set is why the declining fortunes of the vast majority have not touched off social upheaval in America and more turmoil worldwide.

“An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics,” Plutarch wrote two millennia ago. Not much more than two centuries ago the falling fortunes of most Frenchmen brought the monarchy to a sharp-edged end.

The Davos report makes exactly this point in assessing global risks, though in genteel terms:

Structural unemployment and underemployment appear second overall, as many people in both advanced and emerging economies struggle to find jobs. Youth and minorities are especially vulnerable, as youth unemployment rates hover around 50 percent, and underemployment (with low-quality jobs) remains prevalent, especially in emerging and developing markets.

Closely associated in terms of societal risk, income disparity is also among the most worrying of issues. It raises concerns about the Great Recession and the squeezing effect it had on the middle classes in developed economies, while globalization has brought about a polarization of incomes in emerging and developing economies.

The report also warned that the risks from not properly regulating banks threaten the global economy.

“Five years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, with its system-wide impacts, the failure of a major financial mechanism or institution” is cause for deep worry “as uncertainty about the quality of many banks’ assets remains.”

Those words echo the warnings of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, in its detailed and solid report about how systematic fraud on Wall Street sank the economy in 2008. Congress tossed the commission’s thousand-page report in the round file.

Phil Angelides, the California businessman and politician who chaired the panel, says the same thing the Davos report says, but in more dramatic terms. The global financial system is not sound, which means more than a risk that the economy might collapse again.

“It is going to happen again,” Angelides told me.

These findings are not novel, even for the megabanks. What the Davos, Oxfam and other reports say was foreshadowed in a 2005 report by Ajay Kapur, a Citigroup global strategist, about who would prosper in the future and who would not.

Plutonomy is the global future, Citigroup told investors. A plutonomy exists when the wealthy own and consume so much of a society that they render everyone else irrelevant both politically and economically.

(Asserting copyright infringement, Citigroup persuaded numerous websites to remove a follow-up detailed report, many of them after it was highlighted by Michael Moore’s film “Capitalism: A Love Story,” which surely stoked popular revulsion at Kapur’s writing.)

Kapur’s perceptive observations nine years ago included this about capital versus labor:

Despite being in great shape, we think that global capitalists are going to be getting an even greater share of the wealth pie over the next few years, as capitalists benefit disproportionately from globalization and the productivity boom, at the relative expense of labor.

That is sure to cause friction. Jennifer Blanke, the World Economic Forum’s chief economist, warned that “disgruntlement can lead to the dissolution of the fabric of society, especially if young people feel they don’t have a future. This is something that affects everybody.”

What she described is how revolutions start — when young people conclude that the risks and costs of destroying the society they were born into are preferable to letting things continue as they are.

Inequality is here, it is worsening, and if we do not pay attention and change our ways, in time they will be changed for us.