Federal Prison Population Has Increased 800% In 30 Years

The Article: Feds to Reconsider Harsh Prison Terms for Drug Offenders by Sarah Childress in PBS.

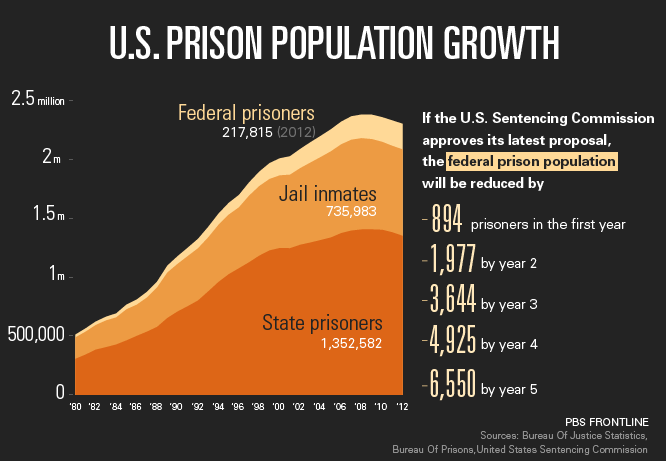

The Text: The federal prison population has expanded by nearly 800 percent in the past 30 years, spurred in part by the increasing use of tougher sentences applied to nonviolent drug crimes.

Now there’s a growing movement to scale it back. On Thursday, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, an independent federal agency, plans to vote on an amendment to sentencing guidelines that could ultimately begin to winnow the federal prison population, nearly half of whom are people convicted of drug offenses.

The amendment is part of a bipartisan push away from America’s addiction to incarceration, which prison reform experts say costs far too much, not only in dollars — $80 billion a year in 2010 — but also in the devastation primarily of African-American communities, who have been disproportionately caught up in the system.

The commission’s proposal would lower the sentencing guideline levels for drug-trafficking offenses, allowing judges to impose reduced sentences by about 11 months, on average, for these crimes. The guidelines are the range between which a judge can sentence an offender. Currently, those guidelines are set higher even than mandatory minimum sentences — the lowest possible sentence a judge could impose — to give prosecutors bargaining power. The amendment would set the upper and lower guideline limits around the mandatory minimums, leading to lower sentences for nearly 70 percent of drug-trafficking offenders, the commission said.

If it passes, the amendment would take effect Nov. 1 and reduce the federal population by 3 percent over the next five years. But it won’t impact the bulk of the prison population, estimated at about 2.2 million in 2012, which is locked up mainly in state prisons and jails.

The amendment would make a difference for people like Dana Bowerman, a Texas honor student who developed a meth addiction at 15, under her father’s influence. When she was 30 years old, Bowerman was arrested with her father and several others and convicted of drug conspiracy charges. Because of the stiff sentencing guidelines, she was sentenced to 19 years and seven months.

Bowerman had committed no violent crimes. She’s since kicked her habit and wants a second chance, according to Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an advocacy group that documented her story. Under the proposed amendment, she would serve 15 years and six months, Julie Stewart, FAMM’s president, said in testimony before the Sentencing Commission.

Prison reform advocates say the commission’s proposal is an incremental step, but an important one. “When you’re serving 10 years, six months can make a difference,” said Jesselyn McCurdy, an attorney with the ACLU’s Washington legislative office. “It’s incremental, but it’s all important because it sends the larger message that we have to do something about the harsh sentencing in the federal system.”

Should the Sentencing Commission’s amendment pass, it will be sent to Congress, which will have 180 days to make any changes. If it does nothing — which is the likely outcome given bipartisan Congressional support for the proposal — the resolution will take effect on Nov. 1.

Model States

For years, states, which carry the bulk of U.S. prisoners, have taken the lead on sentencing reform — largely out of necessity.

Struggling with stretched budgets and overflowing prisons, 40 states have passed laws that ease sentencing guidelines for drug crimes from 2009 to 2013, according to a comprehensive analysis by the Pew Research Center. Seventeen states have invested in reforms like drug treatment and supervision that will save about $4.6 billion over 10 years, according to the Justice Department.

Such reforms also have gained popular public support. According to Pew’s own polling, 63 percent of Americans say that states moving away from mandatory minimum sentencing is a “good thing,” up from 41 percent in 2001. Even more — 67 percent — said that states should focus on treatment, rather than punishment, for people struggling with addiction to illegal drugs.

Federal Intervention

In recent years, the Obama administration has also made moves towards sentencing reform.

In August 2013, Attorney General Eric Holder announced a change in the charging policy for federal prosecutors, instructing them not to charge low-level, non-violent drug crimes with offenses that would trigger a mandatory minimum sentence.

Mandatory minimums offer a one-size-fits-all sentencing. They eliminate the discretion that a prosecutor or judge might otherwise use in determining how to punish an offender based on mitigating circumstances, such as a first-time offender or a low-level, non-violent offense. The number of penalties that carry mandatory minimum sentences has nearly doubled from 98 to 195 over the last 20 years, according to the Sentencing Commission.

There are no proposals to alter mandatory minimums that address violent crimes, such as kidnapping and crimes against children. But a significant number of mandatory minimum sentences involve nonviolent, drug-related offenses, which advocates for reform, and now even some members of Congress, argue end up sending too many first-time offenders to prison for too long. (You can see a full list of federal mandatory minimum sentences here.)

“Many of those mandatory minimums originated right here in this committee room,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), at a recent Judiciary Committee hearing last year. “When I look at the evidence we have now, I realize we were wrong. Our reliance on a one-size-fits-all approach to sentencing has been a great mistake. Mandatory minimums are costly, unfair, and do not make our country safer.”

Prospects for Congressional Reform

The Sentencing Commission itself notes that substantial reform requires action by Congress. “Our proposed approach is modest,” said Patti Saris, the commission’s chairwoman. “The real solution rests with Congress, and we continue to support efforts there to reduce mandatory minimum penalties, consistent with our recent report finding that mandatory minimum penalties are often too severe and sweep too broadly in the drug context, often capturing lower-level players.”

There has been some movement toward reform on both sides of the aisle.

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the sentencing disparity between crack and powdered cocaine, which had been at about 100 to 1 — meaning people, mostly African-Americans, served significantly more time for crack possession than those arrested for possessing the same amount of powdered cocaine. The disparity’s now at 18 to 1.

The Senate is currently considering a bill called the Smarter Sentencing Act, a bipartisan bill introduced in July 2013 by Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) and Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah). It wouldn’t abolish mandatory minimums, but it would allow judges to impose more lenient sentences for certain non-violent drug offenses.

“Our current scheme of mandatory minimum sentences is irrational and wasteful,” Lee said when introducing the bill, adding that the act “takes an important step forward in reducing the financial and human cost of outdated and imprudent sentencing policies.”

It would also allow the Fair Sentencing Act to be applied retroactively to some prisoners, a move that could affect an estimated 8,800 people currently in federal prisons, according to the ACLU. The law would also lower certain mandatory minimum sentences.

But the bill, which even the senators acknowledged as “studied and modest” on their website, doesn’t have great odds of passing. According to govtrack.us, a nonpartisan website that tracks congressional legislation, the Smarter Sentencing Act has only a 39 percent chance of being enacted.