Everything You Need To Know About Syria’s Chemical Weapons

The Article: Everything you need to know about Syria’s chemical weapons by Brad Plumer in The Washington Post.

The Text: The Obama administration’s case for striking Syria hinges on the question of chemical weapons. The Syrian government allegedly used nerve gas on civilians, and that violates long-standing norms. So, the White House argues, the regime needs to be punished.

Mohammad Hannon/AP – Syrian protesters carry a placards showing dead children, during a protest in front of the Syrian embassy to condemn the alleged poison gas attack on the suburbs of Damascus, during a protest in front of the Syrian embassy, in Amman, Jordan, on Friday.

That’s the short version. But let’s step back and unpack this for a moment. Why, exactly, are chemical weapons so horrible? Where did Syria get its weapons? And what is Bashar al-Assad’s regime suspected of doing? Here’s a primer:

What are chemical weapons?

Here’s the official definition: “The term chemical weapon is applied to any toxic chemical or its precursor that can cause death, injury, temporary incapacitation or sensory irritation through its chemical action.”

Chemical weapons are classified according to how they affect human beings: Choking agents like chlorine gas make breathing difficult. Blister agents like mustard gas can cause severe skin and eye irritation. Arsenic- or cyanide-based blood agents are often fast-acting and lethal. Nerve agents like sarin or VX disrupt the nervous system.

There are also plenty of gray areas: Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, riot-control agents such as tear gas are considered chemical weapons if they’re used during war — but not if they’re used for law enforcement. And there are all sorts of technicalities over the use of white phosphorus, an incendiary weapon that has been used in recent years by both the United States and Israel.

Why are chemical weapons considered worse than other types of weapons?

The taboo against chemical weapons is more than a century old. “The primary idea is that they are indiscriminate and an inherent threat to civilian populations,” explained historian Richard Price. “The kernel of that really arose in the aftermath of World War I. Chemical weapons were used on a wide scale in that conflict. There was a real fear, particularly as air technology got better, that there’d be massive chemical attacks on cities.”

Now, granted, regular bombs can be deadly and indiscriminate too. But for a variety of historical reasons, a set of international norms developed around chemical weapons that never developed around conventional explosives. By World War II, most countries had voluntarily ruled out the use of chemical warfare on the battlefield.

Are chemical weapons banned under international law?

Yep. The 1925 Geneva protocol first prohibited the use of poisonous gas as a weapon of war. The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention then went even further and outlawed the production, stockpile, transfer, and use of chemical weapons. Countries that ratified the treaty pledged to destroy their existing stockpiles.

Not everyone has signed that 1993 treaty, however. Syria, North Korea, Egypt, and Angola are notable omissions. Israel and Burma, meanwhile, have signed the treaty but not ratified it.

That said, Syria did sign the 1925 Geneva protocol, which prohibits the use of chemical weapons in war. ”So from a lawyer’s point of view there may be a strong case to be made that Syria violated that earlier legal commitment [if it used chemical weapons during its current conflict],” says Ian Hurd, a political scientist at Northwestern. “It depends what you mean by ‘war’ in that treaty.”

Which countries currently possess chemical weapons?

At least five countries still have officially declared stockpiles: The United States, Russia, Libya, Iraq, and Japan (the latter’s weapons were left in China after World War II). These nations have all pledged to destroy their remaining stocks, but progress has been slow: As of July 2013, there are still more than 13,000 tons of chemical agents left.

That’s not all, though. The U.S. intelligence community believes that Syria, Iran, and North Korea all have their own covert chemical arsenals. Syria, in particular, “maintains a stockpile of numerous chemical agents, including mustard, sarin, and VX.”

There are also a number of other countries that may have chemical weapons or the facilities for producing them, but public information is murky. The list of possible suspects includes: Burma, Egypt, Pakistan, Serbia, Sudan, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

Which countries have used chemical weapons?

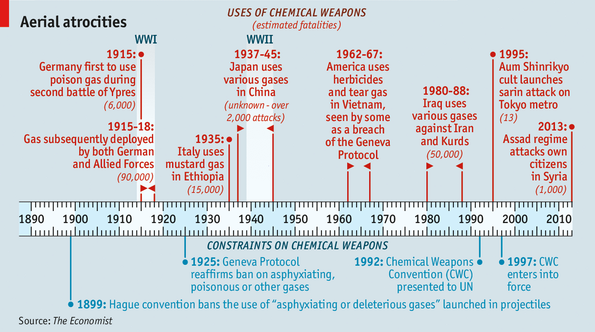

Ancient history records plenty of instances of chemical weapon use — Chinese armies apparently used arsenical smoke back in 1000 BC — but let’s stick with recent times. The Economist has a chart showing the major use of chemical weapons since 1915:

This chart leaves out a few incidents: During the Yemen civil war of 1963-1967, Egypt used mustard gas, phosgene, and tear gas against royalist forces. And in 1987, Libya allegedly used chemical weapons against Chadian troops. See a complete list here.

The most notorious recent incidents have come in Iraq. Saddam Hussein used various gases on a wide scale in his war against Iran and then later in his campaign against Iraq’s Kurds in the late 1980s. His general in that effort, Ali Hassan al-Majid, was given the nickname “Chemical Ali”.

Did Iraq get punished for using chemical weapons?

Not really. “There’s not much of a history of legal enforcement in instances like this,” said Price. “After the Iran-Iraq war, there was no response. All the U.N. could muster was a weakly worded condemnation of chemical weapons that didn’t name names. And the U.S. was in no rush to see Iraq punished, as they didn’t want to see Iran win.”

Later on, however, the U.N. Security Council did pass a number of resolutions to disarm Saddam Hussein. And, in 1998, the U.S. launched Operation Desert Fox, a four-day bombing campaign intended to “degrade” Iraq’s weapons capabilities — chemical, biological, and nuclear — after Hussein kicked out U.N. inspectors.

Let’s move on to Syria. What did the Syrian government supposedly do?

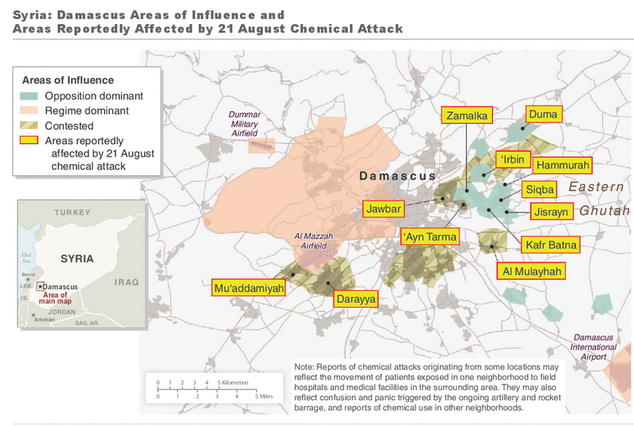

The Obama administration claims that the Syrian government fired rockets loaded with nerve gas on opposition-controlled parts of the Damascus suburbs on August 21, 2013. That attack reportedly killed 1,429 people, including 426 children.

Here’s a map released by the White House of the areas that were allegedly hit:

The administration also said that this wasn’t the first use of chemical weapons in Syria: “We assess with high confidence that the Syrian regime has used chemical weapons on a small scale against the opposition multiple times in the last year, including in the Damascus suburbs.”

What did the nerve gas do to people?

“We have identified one hundred videos attributed to the attack, many of which show large numbers of bodies exhibiting physical signs consistent with, but not unique to, nerve agent exposure,” says the intelligence assessment. “The reported symptoms of victims included unconsciousness, foaming from the nose and mouth, constricted pupils, rapid heartbeat, and difficulty breathing.”

How did Syria get chemical weapons in the first place?

The Syrian government is thought to possess large stocks of nerve agents (sarin and VX) as well as mustard gas, likely weaponized into bombs, shells, and missiles. It also may have some production facilities.

Syria “probably” first began stockpiling chemical weapons in 1972 or 1973, when Egypt gave the country a small number of chemicals and delivery systems before the Yom Kippur War against Israel, according to a recent report (pdf) from the Congressional Research Service.

The Soviet Union later supplied chemical agents, delivery systems, and training. Syria is also “likely to have procured equipment and precursor chemicals from private companies in Western Europe.”

According to the report, Syria doesn’t yet appear to have the capacity to produce the weapons entirely on its own, relying on outside help for precursors.

Just how solid is the intelligence that the Syrian government actually used chemical weapons?

Most of the details are still classified, so it’s hard for the public to know. Secretary of State John Kerry laid out the broad brushstrokes on Tuesday:

We can tell you beyond any reasonable doubt that our evidence proves the Assad regime prepared for this attack, issued instruction to prepare for this attack, warned its own forces to use gas masks.

We have physical evidence of where the rockets came from and when. Not one rocket landed in regime-controlled territory, not one. All of them landed in opposition-controlled or contested territory. We have a map, physical evidence, showing every geographical point of impact, and that is concrete.

… We are certain that none of the opposition has the weapons or capacity to effect a strike of this scale, particularly from the heart of regime territory.

With high confidence, our intelligence community tells us that after the strike the regime issued orders to stop and then fretted openly — we know — about the possibility of U.N. inspectors discovering evidence. So then they began to systematically try to destroy it.

The French government has also released its own assessment, concluding that sarin gas had been used in Damascus and that only the Syrian government could have carried out the attack. That report did not say how certain these conclusions were, however.

Is there reason to doubt the Syrian government used chemical weapons?

One note of skepticism has come from William R. Polk, who served on the State Department’s Policy Planning staff during the Kennedy years. ”Assad had much to lose and his enemies had much to gain [from the use of chemical weapons],” wrote Polk. “That conclusion does not prove who did it, but it should give us pause to find conclusive evidence which we do not now have.”

For what it’s worth, Assad has denied the chemical weapons claim in an interview with the French newspaper Figaro. Russian President Vladimir Putin has also downplayed the charges, saying: “We have no data that those chemical substances—it is not yet clear whether it was chemical weapons or simply some harmful chemical substances—were used precisely by the official government army.”

Can’t independent investigators figure out what happened?

In theory, yes. U.N. inspectors have collected blood samples and other evidence from the Damascus suburbs and are preparing their own report. But that’s likely to take two to three weeks, and may not come out until after a U.S. military strike on Syria.

It’s also not clear how much access the investigators got. The U.N. mission was hindered by the fact that the Syrian military continued to bomb the site in question with conventional weapons after August 21. However, a British intelligence report said that there was likely still some evidence left: “There is no immediate time limit over which environmental or physiological samples would have degraded beyond usefulness.”

So what is the Obama administration now proposing?

The administration is advocating a series of military strikes that are intended to ”hold the Assad regime accountable, degrade its ability to carry out these kinds of attacks, and deter the regime from further use of chemical weapons,” in the words of Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel.

That might entail several rounds of bombing, said Gen. Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — particularly if the Assad regime uses chemical weapons again. ”We’re preparing several target sets, the first of which would set the conditions for follow-on assessments,” he said on Tuesday. “And the others would be used if necessary and on. We haven’t gotten to that point yet.”

Is a military strike the only way to enforce the norm against chemical weapons?

That’s the key question. Richard Price, the historian of chemical weapons, laid out some pros and cons here: “I’m a bit skeptical,” he said. “This immense explosion of outrage and horror around this episode wouldn’t leave a future user of chemical weapons thinking they could just go ahead…. And it’s not as if there are 40 states out there waiting to use these weapons. Only seven or eight states haven’t joined the convention, including Syria, North Korea and Egypt.”

On the other hand, he added, “bombing Syria would be the strongest possible upholding and reinforcement of the norm. Will the norm fall by the wayside if that doesn’t happen? No, I don’t think it will. But if there was a strike to enforce it, that would be a watershed moment in many respects.”

Others have proposed alternatives to military strikes. Rep. Chris Smith (R-N.J.) has suggested setting up an independent court, the Syrian War Crimes Tribunal, to hold Assad accountable for any war crimes committed.

What would happen to Syria’s chemical weapons if the government collapsed?

No one’s really sure. Syria’s weapons and facilities are widely distributed throughout the country. “In the wake of any sudden regime collapse, efforts to find and secure stockpiles would be both a high priority and a difficult challenge,” explained a recent CRS report.

The Pentagon has estimated that it would take more than 75,000 troops to secure Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles, and the United States has reportedly been working with NATO to prepare for several scenarios along these lines.

“Preventing chemical weapons from falling into the hands of extremist elements is the ultimate goal of such policies,” the report notes. “There will continue to be limits, however, to the United States’ ability to monitor the security of these stockpiles and limits to intelligence about where, how well, and by whom they are being secured.”